+ To Kidnap a King (14/04/2016 - 10:58:49)

+ The Historical Association and Elfrida (11/11/2015 - 22:32:56)

+ Author Interview (06/11/2015 - 20:40:53)

+ A Man of Much Wit (06/11/2015 - 20:39:59)

+ Some fabulous reviews of The Temptation of Elizabe (06/11/2015 - 20:36:23)

+ The Temptation of Elizabeth Tudor (06/11/2015 - 20:22:15)

+ Royal Baby: The Spare (29/04/2015 - 07:19:35)

+ Flog It on BBC1 (27/04/2015 - 19:41:04)

+ Childhood Records (22/04/2015 - 14:49:32)

+ Queens Elfrida, Emma and Edith (11/04/2015 - 08:31:21)

+ Queen Eadgifu (10/04/2015 - 07:49:34)

+ Queen Raedburgh (09/04/2015 - 10:12:32)

+ Bertha, Queen of Kent (08/04/2015 - 17:09:43)

+ Back to 1066 (02/04/2015 - 23:02:14)

+ Online Prison Records (27/03/2015 - 20:59:00)

+ England's First Ruling Queen (12/03/2015 - 20:10:58)

+ Happy Birthday Anne Hyde (12/03/2015 - 13:01:31)

+ England's Queens: From Catherine of Aragon to Eliz (12/03/2015 - 12:05:20)

+ Some More Great Reviews (05/03/2015 - 22:01:30)

+ ObituariesHelp.org (19/01/2015 - 20:11:15)

+ England's Queens: From Boudica to Elizabeth of Yor (17/01/2015 - 00:03:16)

+ Online Court Records (16/01/2015 - 23:46:20)

+ Happy New Year (31/12/2014 - 23:55:46)

+ Tudor Times - A New Tudor and Stuart Website (31/12/2014 - 23:49:00)

+ 150 Essential Hints and Tips (02/12/2014 - 19:14:36)

+ Richard III's DNA (02/12/2014 - 19:08:40)

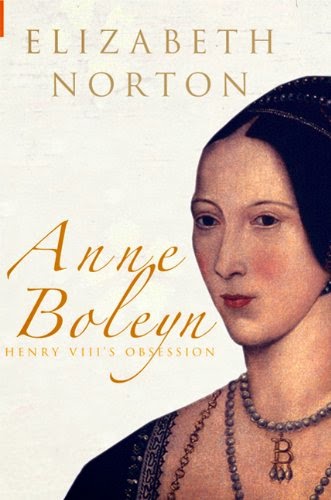

+ The History of the Boleyn Family (13/11/2014 - 20:14:48)

+ Elfrida, The First Crowned Queen of England - Pape (11/11/2014 - 16:17:20)

+ Using Your Local Archives (01/11/2014 - 07:56:14)

+ Who Do You Think You Are? magazine - 10 Simple Ste (01/11/2014 - 07:46:00)

+ Who Do You Think You Are? magazine podcast (01/11/2014 - 07:28:14)

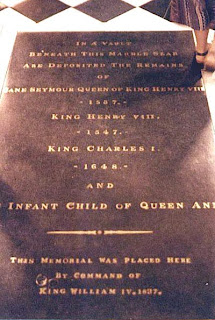

+ Whilst Poor Queen Jane's Body Lay Cold Under Earth (25/10/2014 - 13:45:07)

+ The Death of Queen Jane (24/10/2014 - 21:22:57)

+ Jane's Last Night (23/10/2014 - 06:58:23)

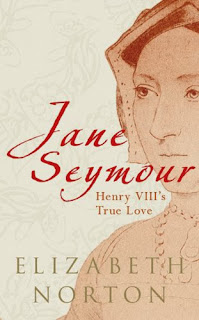

+ Who was Jane Seymour? (22/10/2014 - 06:57:01)

+ Jane Seymour's Health (21/10/2014 - 01:30:30)

+ Bound to Obey and Serve (20/10/2014 - 20:06:00)

+ Childbed Fever (19/10/2014 - 23:30:07)

+ Not of Woman Born? (18/10/2014 - 10:37:36)

+ Jane Seymour: Crisis Point (17/10/2014 - 20:28:32)

+ 'Suffered to Take Great Cold' (16/10/2014 - 12:13:28)

+ The Boleyn Women (15/10/2014 - 17:29:20)

+ Prince Edward's Christening (15/10/2014 - 16:21:57)

+ Preparing for a Royal Christening (14/10/2014 - 11:26:20)

+ A Royal Birth Announcement (13/10/2014 - 11:20:19)

+ Happy Birthday Edward VI (12/10/2014 - 22:12:31)

+ Medieval Warfare Magazine - Book Review (09/10/2014 - 23:05:31)

+ BBC History Magazine: Queens of England Quiz (09/10/2014 - 23:01:34)

+ BBC History Magazine: 10 things you (probably) did (16/09/2014 - 13:42:32)

+ Oscar Best Picture Winners: The Godfather (1972) (11/09/2014 - 21:16:33)

+ The Tudor Treasury (11/09/2014 - 20:55:05)

+ The 10 Best Queens in English History (11/09/2014 - 20:54:19)

+ The Blounts of the West Midlands: Reformation Reli (11/09/2014 - 20:40:46)

+ Catholic Records (11/09/2014 - 20:36:55)

+ The Depiction of Children on Fifteenth and Sixteen (01/09/2014 - 21:57:36)

+ Moving On... (01/09/2014 - 15:37:43)

+ Some nice reviews! (31/08/2014 - 21:14:16)

+ Queen Anne, First Monarch of Great Britain (08/08/2014 - 21:15:24)

+ From Peasant to Princess in Six Generations (10/07/2014 - 21:17:01)

+ Looking Online: Find Old Records (09/07/2014 - 21:18:38)

+ Tudor Matchmaking (Part 3) (29/06/2014 - 21:20:02)

+ Tudor Matchmaking (again) (28/06/2014 - 21:21:12)

+ Tudor Matchmaking (27/06/2014 - 21:24:07)

+ Oscar Best Picture Winners Challenge: Cimarron (19 (27/06/2014 - 21:22:33)

+ Find Your Family For Free (14/06/2014 - 21:25:22)

+ BBC History magazine: Jane Seymour (10/06/2014 - 21:26:38)

+ BBC History Magazine: Anne Boleyn in Profile (29/05/2014 - 16:25:30)

+ Oscar Best Picture Winners: Argo (2013) (29/05/2014 - 16:24:02)

+ Bloody Tales of the Tower on Channel 5 (23/05/2014 - 16:26:37)

+ Workhouses and Institutions (21/05/2014 - 16:27:17)

+ 20 May 1536 - The Betrothal of Henry VIII and Jane (20/05/2014 - 16:29:47)

+ Anne Boleyn and Henry Percy (20/05/2014 - 16:28:35)

+ 19 May 1536 - The Execution of Anne Boleyn (19/05/2014 - 16:31:10)

+ 18 May 1536 - I thought then to be dead (18/05/2014 - 13:38:31)

+ Oscar Best Picture Challenge: Grand Hotel (1932) (17/05/2014 - 13:40:42)

+ 17 May 1536 - The Thunder Rolls (17/05/2014 - 13:39:21)

+ 16 May 1536 - Last days (16/05/2014 - 13:42:11)

+ 15 May 1536 - A Trial at Last (15/05/2014 - 13:43:57)

+ 14 May 1536 - Thomas Cromwell (14/05/2014 - 13:46:55)

+ 13 May 1536 - No longer Anne the Queen (13/05/2014 - 13:48:30)

+ 12 May 1536 - The Trials of Smeaton, Norris, Westo (12/05/2014 - 13:49:42)

+ 11 May 1536 - Lady Wingfield and Lady Worcester (11/05/2014 - 13:51:49)

+ 10 May 1536 - Lady Rochford (10/05/2014 - 13:54:09)

+ Inside the Tudor Court (10/05/2014 - 13:52:47)